Architecture trabéculaire et mode de vie volumes d’intérêt dans les métaphyses humérales des reptiles non-aviens (Plasse et al. 2019)

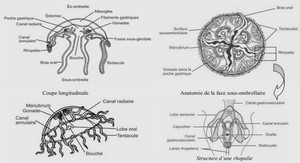

Ce chapitre traite de la relation entre l’architecture trabéculaire et le mode de vie chez trois groupes de reptiles actuels (crocodiles, « lézards » et tortues). Des volumes d’intérêt sphériques ont été extraits à l’intérieur des humérus proximaux. Douze paramètres trabéculaires (épaisseur, longueur, fraction volumique osseuse…) ont été calculés et comparés entre les modes de vie. L’hypothèse suivante est également avancée : les espèces terrestres auraient une orientation préférentielle des travées, plus que celles qui sont amphibies et davantage que les aquatiques. Des informations concernant les allométries des travées et leurs signaux phylogénétiques (liés aux relations de parenté entre espèces) ont été égale- ment obtenues. Trabecular architecture in the humeral metaphyses of non-avian reptiles (Crocodylia, Squamata and Testudines) : Lifestyle, allometry and phylogeny. Journal of Morphology, 280, 982-998. The lifestyle of extinct tetrapods is often difficult to assess when clear morphological adaptations such as swimming paddles are absent. According to the hypothesis of bone functional adaptation, the architecture of trabecular bone adapts sensitively to physio- logical loadings. Previous studies have already shown a clear relation between trabecu- lar architecture and locomotor behavior, mainly in mammals and birds. However, a link between trabecular architecture and lifestyle has rarely been examined. Here, we ana- lyzed trabecular architecture of different clades of reptiles characterized by a wide range of lifestyles (aquatic, amphibious, generalist terrestrial, fossorial, and climbing).

Humeri of squamates, turtles, and crocodylians have been scanned with microcomputed tomography. We selected spherical volumes of interest centered in the proximal meta- physes and measured trabecular spacing, thickness and number, degree of anisotropy, average branch length, bone volume fraction, bone surface density, and connectivity density. Only bone volume fraction showed a significant phylogenetic signal and its sig- nificant difference between squamates and other reptiles could be linked to their physi- ologies. We found negative allometric relationships for trabecular thickness and spacing, positive allometries for connectivity density and trabecular number and no dependence with size for degree of anisotropy and bone volume fraction. The different lifestyles are well separated in the morphological space using linear discriminant ana- lyses, but a cross-validation procedure indicated a limited predictive ability of the model. The trabecular bone anisotropy has shown a gradient in turtles and in squamates: higher values in amphibious than terrestrial taxa. These allometric scalings, previously empha- sized in mammals and birds, seem to be valid for all amniotes. Discriminant analysis has offered, to some extent, a distinction of lifestyles, which however remains difficult to strictly discriminate. Trabecular architecture seems to be a promising tool to infer life- style of extinct tetrapods, especially those involved in the terrestrialization.

Bone is a tissue able to adapt to its external mechanical environment. This seminal insight, commonly referred to as “bone functional adaptation,” has been originally described by Wilhelm Roux (Roux, 1885). Within the bones, trabecular architecture is more responsive and malleable to external loads (for a review see Cowin, 1998, Kivell, 2016). During bone modeling, osteocytes embedded in the bone matrix act as mechano-sensors and send strain-related signals to other cells (Huiskes, Ruimerman, Van Lenthe, & Janssen, 2000). They recruit osteoblasts, which create bone, and osteoclasts, which resorb bone (Gerhard, Webster, Van Lenthe, & Müller, 2009), processes which result in bone functional adaptation (Martin, Burr, Sharkey, & Fyhrie, 2015). A change of loading regimes on bone can modify the trabecular architecture. Many experimental studies support this hypothesis. For instance, macaques trained to walk bipedally have shown significantly different shape of femur and ilium than wild (quadrupedal) ones (Volpato, Viola, Nakatsukasa, Bondioli, & Macchiarelli, 2008). There- fore, different locomotor behaviors may leave different signatures inside bones. Indeed, in the above-cited bipedally trained macaque, the trabecular architecture of the iliac body became more anisotropic, thicker, and more structured vertically oriented (Volpato et al., 2008).

In the same way, sheep exercised daily to trot on inclined treadmills have developed thicker trabeculae with a higher bone volume fraction in their distal radius (Barak, Lieberman, & Hublin, 2011). A similar adaptation in trabecular architecture has been shown in rabbits by the application of in vivo cyclic loading on the hind limbs (van der Meulen et al., 2006).analysis focused on the humeral and femoral head of four primates species, terrestrial taxa have shown more anisotropic trabecular archi- tecture in comparison to arboreal ones (Fajardo & Müller, 2001). In another broader study on anthropoid primates, trabecular architecture from the humeral and femoral heads was found to be similar in arbo- real and terrestrial locomotor groups (Ryan & Shaw, 2012). In a study focused on the fore limb epiphyses of xenarthrans, trabeculae have shown the clearest functional signal through their anisotropy: armadil- los, fully terrestrial and fossorial, have the most anisotropic trabecular architecture in xenarthrans (Amson, Arnold, van Heteren, Canoville, & Nyakatura, 2017). In a study focused on the sciuromorph femoral head, four trabecular parameters have shown functional signals related to the various lifestyles found in this clade (Mielke et al., 2018).