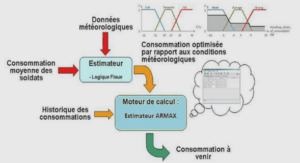

Framework for Water Demand Forecasting

A set of water demand forecasting literature differentiates forecast practice by the level of planning associated with the forecast (Gardiner and Herrington, 1990), or in accordance with the forecast horizon (Billings and Jones, 2008). In terms of planning level, all water demand forecasting exercises can be used either for strategic, tactical or operational decision making. These respectively concern decisions for capacity expansion, investment planning and system operation, management and optimization. In terms of forecast horizon, water demand forecasting can be categorized as either long-term, medium-term or short-term with these horizons being reflective of the general purpose of the forecast. Long-term, medium-term and short-term forecasts are prepared for strategic, tactical and operational decisions respectively (Ghiassi, Zimbra, and Saidane, 2008). No generally accepted time frame exists for these horizons. For instance, Billings and Jones, 2008 contain different time horizons regarding what constitutes long-term, medium-term and short-term forecasts. One such definition classifies forecasts spanning more than 2 years as long-term, those from 3 months to less than 2 years as medium-term, and forecasts for 1 to 3 months as short-term. (Bougadis et al., 2005; Li and Huicheng, 2010; Nasseri et al., 2011; Donker et al., 2014 and Rinaudo, 2015). This contrasts with Gardner and Herrington, 1990 who classify these categories as annual forecasts for 10 years or more, annual forecasts for 1 to less than 10 years, and hourly to monthly forecasts up to a year. In terms of application, Ghiassi et al., 2008 prepared monthly demand forecasts for 2 years, weekly demand forecasts for 6 months and daily demand forecasts for 2 weeks, and characterize these as long-term, medium-term and short-term respectively. Researchers focused on forecasting single-family residential water use where the urban lifestyle is heavy oriented toward single-family homes (Wentz et al., 2014; Ouyang et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2017).

Household Water Consumption Variables and Determinants

Apart from the various planning levels and horizons that tend to complicate urban water demand forecasting, the forecast variable of interest and the determinants of water use are two features that add to the complexity. In the drinking water community, many variables are considered influential in determining water consumption. Although “A good understanding of the factors influencing demand and reliable estimates of the parameters describing demand behavior and consumption patterns are prerequisites [to a good forecast]” (Burney et al., 2001). The enormity of these variables can create frustration for water utility mangers. As an illustration of the size and variability of the variables that can be considered, we refer to a report prepared for the Water Research Foundation by Coomes et al., 2010, in which the authors tested the effect of 26 variables on average daily water use for 293 residential customers of the Louisville Water Company. Besides, in the present research we tested 24 variables on trimester water consumption for 201 individual houses in Sedrata City, Souk Ahras. According to researchers, there are several factors known as drivers or explanatory variables affecting the water consumption. These include socio-economic parameters (population, income, water tariff, etc.), physical characteristics of housing units (area of the house, garden size, etc.), weather data (temperature, precipitation, etc.), study-site infrastructure and system (productivity, technology, etc.), political and administrative factors (application programs, education, and cost) (Gato et al., 2007; Billings and Jones, 2011 and Tiwari and Adamowski, 2013), as well as cultural factors such as consumer preferences and habits. These factors determine water consumption, which means they should be considered input data for forecasting.

Socio-economic parameters

It is imperative to understand what socio-economic and demographic factors. Most empirical studies Renwick and Archibald, 1998; Mayer and DeOreo, 1999; Turner et al., 2009; Beal and Stewart, 2011; Fielding et al., 2012; Halper et al., 2012; Beal et al., 2013; Ouyang et al. 2013; Willis et al., 2013; Matos et al., 2014; Hussein et al., 2016 and Fan et al., 2017 have found residential demand or use for water is influenced by heterogeneity associated with differences in the size of the household and socioeconomic characteristics. The most significant can be categorized into:

Household income and water price

Household income has been reported to have a variety of relationships with water consumption (Nieswiadomy and Molina, 1989; Arbues and Villanuà, 2006; Guhathakurta and Gober, 2007; March and Saurf, 2010; Qi and Chang, 2011; Fielding et al., 2012 and Anas et al., 2014). Authors like Kenney et al., 2008; Schleich and Hillenbrand, 2009; Moffat et al. 2011 and Grafton et al., 2011 found that households with greater incomes have greater household water consumption than households with lower incomes, due mainly to much higher discretionary irrigation end-use demand. But, Beal et al., 2011a outlined a trend of larger, highincome households using less water per capita than smaller, low-income households. The conflicting results highlight the importance of reporting water demand in water end-use categories (e.g., shower use) and on a per capita basis. 1.3.1.2.Household size Family size has a variety relationship with water consumption (Arbuès et al., 2010; Beal et al., 2011a; Gato, 2011; Makki et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012). It has been reported in previous studies that the increase in household water consumption is associated with an increase in the number of people in the household as Beal et al., 2011b; Beal and Stewart, 2011 and GatoTrinidad et al., 2011), because in general more people use more water. In contrast, it has been found that household per capita consumption decreases as household size increases, due to economies of scale (Beal et al., 2011b; Beal and Stewart, 2011; Russell and Fielding, 2010 and Turner et al., 2009).

Retired person

Total indoor water consumption in households with working residents is significantly higher than that in households with retired residents, and this is mainly due to shower, clothes washer and dishwasher end-use consumption categories (Beal and Stewart, 2011; Beal et al., 2012b, Makki et al., 2011 and Makki et al., 2013). Lyman, 1992 and Willis et al., 2009 hypothesised that retired individuals spend a relatively greater proportion of their time at home and thus have a greater opportunity to use water-dependent appliances.

Sex (Gender)

(1 = female and 0 otherwise) is supposed to affect WCP. A positive relationship between WCP and GEN might exist when the respondent is female because they are the ones who take care of domestic household chores such as travelling to other places to fetch water in times of need, hence they will be willing to pay (Moffat et al., 2011)

Number of women

Number of women was found to have an effect on indoor water use because women spend more time at home more than men (Mu et al., 1990).

Age

distribution of household members WCP for improved water quality and reliability of supply is expected to be positively related to education. The longer time in formal schooling (years), the more people understand better the consequences of using unsafe water and the need to have reliable water supply. Therefore, the educated will be more willing to pay than the illiterate (Moffat et al., 2011). A study showed that houses with children may have higher water demand as children are more likely to use lawns for play and recreation (Hurd, 2006 and Balling et al., 2008). Although, children may use less water than adults for washing and hygiene (Schleich and Hillenbrand, 2009). Other studies outlined that teenager was the key variable of per capita water demand (Schleich and Hillenbrand 2009 and Aquacraft 2015). People of different ages tend to demonstrate different water- related behaviours at home (Makki et al., 2011). There are conflicting results about the effects of age distribution in previous studies. Some, such as Nauges and Thomas, 2000; Martınez-Espineira, 2003; Martins and Fortunato, 2007 and Musolesi and Nosvelli, 2007, find a negative relationship between per capita water use and the share of elderly people living in households, while other studies, such as Fox et al., 2009; Schleich and Hillenbrand, 2009 and Beal et al., 2011a find that older people and retired individuals (Lyman, 1992 and Willis et al., 2009) use more water in their homes. Families with children could be expected to use more water. Outdoors use by children and teenagers might be higher too. Youngsters might use water less carefully, have more showers, and demand more frequent laundering, while retired people might be thriftier. These expectations are confirmed by studies like Nauges and Thomas, 2000 and Kenney et al., 2008 observed that as the mean age of a household increases, so does household water consumption. Chapter 01: Literature Review 12 Kenney et al., 2008 also outlined the correlation between age, household income and wealth, noting that the increase of water consumption per household is a result of the combination of these variables. Contradictory to previous studies, Wentz et al., 2014 found that age of people was not a significant factor affecting water use. It is well documented that the increase of water use with the increasing in number of occupants is by no means a linear relationship (Heinrich, 2009; Beal et al., 2011a; Gato, 2011 and Lee et al., 2012).