LES CONFIGURATIONS A LOCALISATION DEGRADEE

INTRODUCTION

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease caused by spirochetes of the genus Leptospira. Leptospires infect and develop inside renal tubules of a variety of Vertebrates, essentially mammals, notably rodents, which excrete the pathogen into the external environment. Humans are infected following contact with contaminated water or humid soils. Symptoms range from null to very severe and death (reviewed in Haake & Levett 2015). It is considered that one million cases occur annually in the world, among which 60,000 have fatal issues (Costa et al. 2015). Leptospirosis has been mainly associated with rice agriculture and breeding as well as water recreational activities (Mwachui et al. 2015). Flooding episodes may also trigger local leptospiral epidemics (e.g., Thaipadungpanit et al. 2013), with one out of eight flood event-associated epidemics being due to leptospirosis (Cann et al. 2013). In addition, more and more evidence suggest that the disease may occur in urban settings, especially socio-economically disadvantaged, informal and poorly sanitated ones, such as slums (e.g., Ko et al. 1999; Cornwall et al. 2016), sometimes with higher waterborne leptospires concentrations compared to surrounding rural areas (e.g. in Peru, Ganoza et al. 2006). As a consequence, ongoing urbanization together with multiplying extreme climatic events are expected to increase the risk of human leptospirosis (Lau et al. 2010). This may be particularly true in Africa where the disease is present but yet remains poorly documented (reviews in de Vries et al. 2014; Allan et al. 2015). In particular, we are aware of no study focusing on soil- or waterborne leptospires in Africa (see Tab. 2 in the review by Bierque et al. 2020). The so-called « Abidjan-Lagos corridor » (ALC) is a 700km-long conurbation that sprawls along the West African Atlantic coast. It currently houses >25 million people who live within and in the surroundings of large adjacent cities such as Lagos (11.8 million inhabitants), Porto-Novo (570,000 inhabitants), Cotonou (1.5 million inhabitants), Lomé (1.7 million inhabitants), Accra (4.4 million inhabitants) and Abidjan (4.7 million inhabitant) (2015 data; OECD/Africapolis project, www.africapolis.org, 2020). It is expected to reach ca. 34 million city dwellers by 2025 (UN Habitat, 2014). This very rapid and mostly uncontrolled urbanization translates into the creation and expansion of vast socially disadvantaged areas where pollution, access to basic services (e.g., health care, education, transport, sanitation, waste management) and acceptable housing conditions are rare, thus raising important environmental and health issues. In addition, the ALC comprises many lakes, mangroves and swamps which form a dense hydrographic network. Together with a subequatorial climate, low altitude and flatness, this makes this West African coastal region extremely susceptible to flooding events. For instance, 43% of Cotonou, Benin, is flooded one to two months a year either following Lake Nokoué overflows or rain accumulation in shallows. Such episodes directly affect 200,000 inhabitants and indirectly impact many others through service interruption, resource unavailability or degraded water quality (PCUG3C, 2010; Houéménou et al. 2019b). In addition, they are often enhanced by poor drainage due to defective or crowded sanitation network as well as anarchic land use (PCUG3C, 2010).These conditions as well as the omnipresence of anthropophilous rodents (Houéménou et al. 2019a) elevate the risk of leptospiral contamination in the ALC (Dobigny et al. 2018). Accordingly, up to 18.9% of commensal rodents were found pathogenic Leptospira-positive in cities from south Benin (Houéménou et al. 2014, 2019a), suggesting that leptospires may massively circulate in the ALC urban environment. Mean annual temperatures (ca. 27°C) and rainfalls (ca. 800-1,600mm) are highly favorable to Leptospira survival. However, although waters and humid soils appear as the corner stone of human contamination (Barragan et al. 2017; Bierque et al. 2020), little is known about the precise environmental conditions that are compatible with pathogenic Leptospira outside of its mammalian host (see for instance Chang et al. 1948; Gordon-Smith & Turner 1961; Khairani-Bejo et al. 2004; WojcikFatla et al. 2014; André-Fontaine et al. 2015; reviewed in Barragan et al. 2017 and Bierque et al. 2020), especially in urban habitats where pollution may be very important (Lapworth et al. 2017). The present study aims are: (i) to confirm the presence of pathogenic leptospires out of their hosts in Cotonou waters, (ii) to determine the physico-characteristics of waters where it was found, and (iii) to compare these physico-characteristics with the chemical spectrum of all waters within the city. Altogether, our preliminary data allow us to explore for the first time the ability of leptospires to evolve in water within an urban polluted habitat in Africa.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

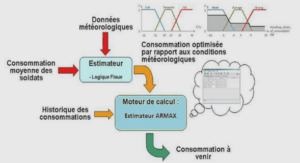

Study area and sampling Cotonou town is located in the coastal sandy plain of Benin between the Atlantic Ocean at the south and Lake Nokoué at the north (Fig. 1). The littoral zone in the south of Benin is characterized by a subequatorial climate. The average annual rainfall for Cotonou is 1,300 mm (Yabi and Afouda, 2012). Seasonal variations during the year are marked by a large rainy season from mid-March to mid-July followed by a small rainy season from mid-September to mid-November alternated, respectively, by a small dry season from mid-July to mid-September and a large dry season from mid-November to midMarch. The study area involves 3 districts located in the core city of Cotonou: Ladji, Agla and Saint Jean (Fig. 1a) that are distinct in the sources and duration of inundation and pond waters. Ladji is located at the edge as well as upon the Lake Nokoué, thus displaying houses built both on hard ground and on stilt pegs (Fig. 1b). Lacustrine waters are permanent, but flooding of zones adjacent to the lake only occurs at the end of the rainy season (i.e., September and October) following the rise in lake levels. Therefore, the area has both long-standing lake water and temporary pond waters. Permanent ponds are also present due to dry season groundwater discharge (Houéménou et al. 2019b). Ladji is densely populated, has essentially informal housing development and is a very poor area where even the most basic public services are usually missing. In particular, waste management is almost inexistent, garbage are omnipresent and are even often used as embankment material. Such an environment favors proliferation of rodents, which are abundant and infest 60-100% of households depending on the season (Dobigny et al. 2019). Agla is a recent but rapidly expanding district within a vast lowland that is extensively flooded early in the rainy season (i.e., starting from June) following rainfall accumulation. Similar to Ladji, permanent ponds are also present in Agla due to the extensive low-lying areas. The permanent ponds are formed by groundwater discharge in the dry months, whereas during the winter months the rainfall inputs to the ponds reverse the hydraulic gradients, resulting in groundwater recharge ponds (Houéménou et al. 2019b). The habitat in Agla includes hard-built houses as well as very precarious cabins, with the poorest inhabitants usually gathering around or within these floodable low-lying areas (Fig. 1b). These low-lying areas are also widely used as dumping sites for household waste (Fig. 1b). Rodents are abundant in households, with infestation rates always ≥ 90% (Dobigny et al. 2019). Saint-Jean is an old and formal district that has large open sewers and many houses that are solidly constructed. This district is not floodable per se, but large ponds may stand for several days after heavy rains. Rodents are also abundant in ca. 90% of households (Dobigny et al. 2019). In 2017 and 2018, the three districts of Cotonou (Agla, Ladji and Saint Jean; Fig.1b) were monitored for both water quality parameters (physical parameters, major ions and trace elements) and leptospire presence. Water sampling was organized concomitantly (i.e. within the same week) in the three districts during the dry season (March 2017 and February 2018) as well as at the beginning (June 2017 and June 2018) and at the end (October 2017) of the rainy season. In total, 193 water samples were collected: 85 in Agla, 53 in Ladji and 55 in Saint Jean. Eighty-three samples were tap waters and 61, 29, 17 and 3 samples were from groundwater wells, temporary ponds, permanent ponds and Lake Nokoué, respectively. This corresponds to 51, 64, 55, 5 and 18 samples collected in March 2017, June 2017, October 2017, February 2018 and June 2018, respectively. The detailed distribution of samples among districts, periods and water types are provided in Table 1. The temporary ponds were differentiated from the permanent ponds by noting locations where the waters were present in the wet season but not in the dry season. Both temporary and permanent ponds were sampled in Ladji (8 and 6, respectively) and Agla (21 and 11, respectively), but not in St Jean where ponds only last a few days. Nous effectuons une analyse en composantes principales sur les quatre critères suivants: émissions dues au stockage et au transport, nombre de produits stockés, nombre de kilomètres.Nous considérons d’après les trois critères de l’analyse que les deux premières valeurs propres sont suffisantes .Le premier axe représente les émissions donc les critères environnementaux et l’axe 2 oppose les critères financiers Sur la figure 63, nous confirmons que les configurations en lll et ses dégradations avec une localisation r émettent moins que les autres configurations. De même, la configuration globale est celle qui émet le plus. Par contre, les autres classes méritent des explications car les résultats ne sont pas forcément triviaux. Les configurations dégradées en c de lll sont équivalentes à une configuration entièrement régionale. Si, nous nous intéressons aux configurations continentales, nous voyons que dès que celle-ci est dégradée avec une localisation globale le nombre de kilomètres et les émissions augmentent quelle que soit la place de la dégradation de même la configuration régionale et ses dégradations avec une configuration continentale. Les dégradations des configurations locale et régionale avec une configuration globale apportent une information intéressante : les configurations où la localisation globale est en position finale sont moins émettrices que les configurations où cette localisation est en amont. Nous réalisons un focus sur ces configurations à la figure 64, zoom de la figure 63. Nous voyons alors nettement d’après le tableau 38 que les configurations ayant un g en dernière position émettent environ 6 fois moins que les mêmes configurations ayant un g positionné en première ou deuxième position. De même, leur nombre de kilomètres est moindre. Nous pouvons l’expliquer de la manière suivante. Nous avons paramétré notre modèle pour un taux de service de 100%. Les stocks et les niveaux de sécurité de ceux-ci sont paramétrés en conséquence. Lorsque la localisation globale se situe en première ou seconde position, les transports express, plus émetteurs que les transports classiques, se déclenchent pour livrer la dernière entreprise afin que celle-ci puisse livrer à l’heure le client final. Lorsque le client final se situe très loin de la dernière entreprise, nous pouvons émettre l’hypothèse suivante. S’il y a rebuts, les commandes de produits se répercutent sur les entreprises précédentes. Celles-ci sont susceptibles d’accuser des retards. Si leur localisation n’est pas continentale ou globale, il n’y a pas de transports express. Les stocks de la dernière entreprise en localisation globale sont quant à eux dimensionnés pour assurer un taux de service de 100%. Si quelques transports express peuvent se déclencher, ils sont cependant marginaux. D’autres hypothèses de départ auraient pu être choisies et feront l’objet d’un développement dans les perspectives de recherches.

Configurations AAA, 4 produits, localisation dégradée

Nous reprenons donc les 22 configurations précédentes en les appliquant aux quatre types de produits. Si nous effectuons une classification par analyse des composantes principales, nous obtenons les résultats suivants (tableaux 39 à 41 et figure 65). Nous concluons que les deux premières valeurs propres, d’après les trois critères nécessaires et suffisants (variance, scree test, test de Kaiser), sont assez représentatives comme l’indique le tableau 39 L’axe 1 caractérise le stockage tandis que l’axe 2 oppose les facteurs financiers aux facteurs environnementaux. Après projection sur ces axes, nous répartissons les 88 configurations entre cinq classes.Nous représentons ces cinq classes sur la figure 65. Nous constatons que le type de produits est très influent. Les produits 1 et 2 sont dans les mêmes classes. Puis plus la dégradation est forte plus les classes se translatent vers le haut et la droite. Les résultats des émissions des produits 3 et 4 sont très importants et prennent le dessus par rapport aux autres facteurs. Un point est à noter : la présence dans la même classe des produits 1 et 2 en configuration ccc et des produits 3 et 4. Nous pouvons expliquer ce point par le nombre de kilomètres parcourus en camion et non en bateau comme dans la configuration ggg. En effet, le bateau émet du CO2 en quantité moindre par rapport au camion. Le type de produits ne compense pas cette différence. Par exemple, une configuration cgc avec le produit 1 émettra donc moins en terme d’émissions dues au transport qu’une configuration ccc. En simplifiant, nous aurions 8000 kilomètres multipliés par un facteur d’émissions de 3.57 soit 28 560 contre 1600 kilomètres par 74.90 soit 119 840.

Configurations à efficacité homogène, quatre produits, localisation dégradée

Nous traitons les 352 simulations avec une classification hiérarchique sur les quatre critères quantitatifs suivants : émissions dues au transport et au stockage, nombre de kilomètres et nombre de produits stockés. Si nous établissons une classification hiérarchique uniquement pour les configurations à efficience AAA et DDD, nous obtenons cinq classes dont les barycentres sont décrits dans le tableau 42. configurations lll, produit 1 à efficacité dégradée Les huit configurations sont dues à l’introduction dans une chaîne AAA d’un maillon dégradé D, puis de deux maillons dégradés DD, puis de trois DDD : Les résultats de la classification par la méthode des centres mobiles sont donnés au tableau 45 et à la figure 67 selon : – les émissions dues au stockage en tonnes équivalent CO2 – les émissions dues au transport en tonnes équivalent CO2.